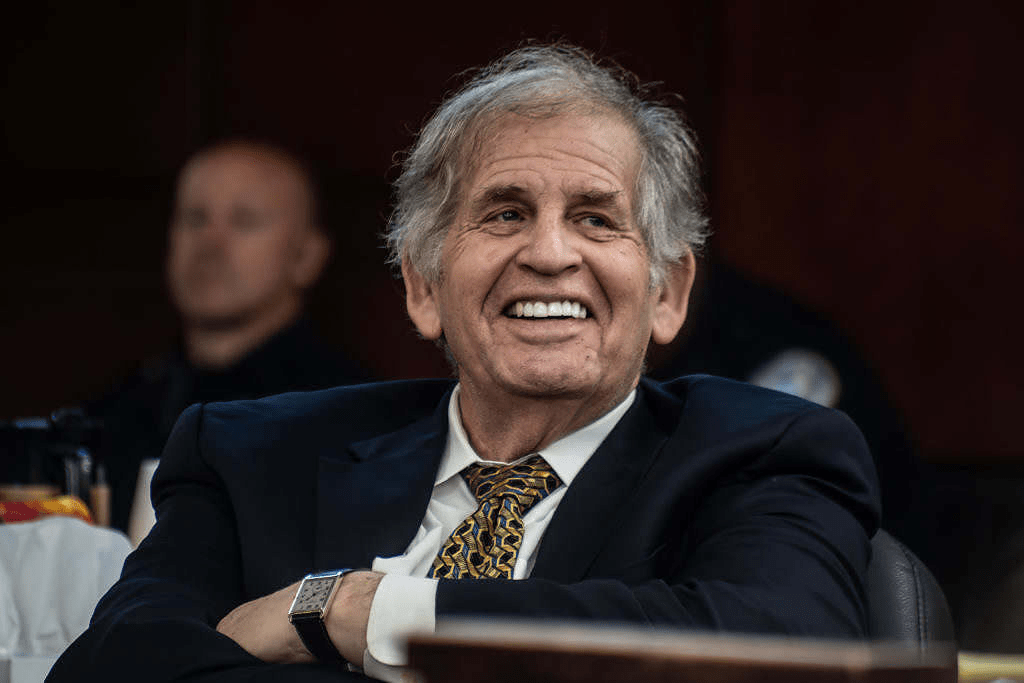

Jack Swerling, Esquire

This time of year I think about the Valentine’s Day defense in a murder case I was once part of. An upstate doctor, known for bragging about his gold coin collection, and his wife were brutally murdered. The police had no clues and the murders faded from the headlines without an arrest until, almost a year later, a snitch bargained his way out of a burglary by offering up our client as the perpetrator of the murders. Our client was arrested in Philadelphia, extradited to South Carolina, and, considered to be real badass, was being held pending trial in the notorious Central Correctional Institution (CCI) in Columbia.

Lead defense counsel, Jack Swerling, sent me over to CCI to see our client, tell him about his upcoming trial date, and that I was headed up to Delaware to get the records he had told us about. To get to CCI, you had to park in lot across US Highway 1 and walk a catwalk over the highway to the prison gate. It was my first time going to CCI so I couldn’t help but notice how much it looked like an old castle complete with battlements on top of its walls. Then I reminded myself General Sherman had quartered his horses in the very same building on his march to the sea during the Civil War.

Once inside the guard house, and once you established you were indeed a lawyer, on official legal business, and had, in fact, called to schedule an inmate visit, you would be let in to the prison and assigned a guard to escort you to the attorney conference area. Walking down the hall my escort pulled me aside so an inmate later identified as Pee Wee Gaskins could pass by. I didn’t know who he was but sure noticed the way the crowd parted in the hallway when he walked by. I was escorted to an attorney conference where I met with our client . He was seated behind a small desk with his hands handcuffed through a loop in the metal desk. I was struck that he seemed completely unfazed about being held in CCI.

I don’t think he said three words to me as I nervously rattled off all the things I been instructed to tell him. I told him I had been given the task of taking an Order signed by a judge here in South Carolina up to Delaware and of finding a judge up there to countersign the Order so I could get the Clerk of Court in Delaware to issue a subpoena for the auto repair shop records we wanted to get copies of. I was glad he didn’t have any questions when I finished because I had no idea what I was doing. I buzzed for the guard come let me out and take me back to the gate.

Our client pled not guilty to the murder and claimed the snitch who’d implicated him was originally from Philly and would periodically bring stolen property up from South Carolina to fence it. One time, the snitch thought he’d hit it big time and brought up a whole tractor/trailer full of stolen cigarettes. The snitch gave the keys to the truck to our client who promised to come right back with the cash but ripped him off instead. He said the snitch was just trying to settle the score by blaming him for the murder the snitch probably committed.

The snitch’s story was specific, too specific. He said he told our client about the doctor’s coin collection and our client drove his light blue Cadillac DeVille down to South Carolina from Philly to rob the doctor. Our client said the snitch was lying because his Cadillac was in the shop getting a new windshield on the day of the murders. He knew this because he’d forgotten to buy his girlfriend a Valentine’s Day present so she put a brick through the windshield. In Delaware all cars have sequentially numbered inspection stickers on the windshield. When a new inspection sticker is issued, it has to be entered in a master record book the shop owner was required to keep. I was being sent to Delaware to fetch the official records which would prove our client’s car was in the shop at the time of the murders and our client’s innocence.

I felt like a real lawyer flying a jet to Philly, renting a car on the law firm credit card, and finding my way to the Kent County Courthouse in Deleware. And, there I found a welcoming Judge willing to sign off on the order. I felt like I’d done the impossible. The rest of the trip was easy just following through getting a subpoena from the Clerk, driving to the repair shop, and picking up certified copies of the official records. As I flew home later that same night, I dismissed the thought it was almost too easy.

My job was done. It was for lead counsel to decide how best to use the documents during trial. Watching him, I learned the importance of boxing a witness in on cross examination. “Boxing” is the methodical blocking off of all avenues of escape a witness may have before springing a trap on cross examination. It not only prevents a weasling witness from getting away from a lie, it dramatically enhances the impact of the evidence he’s lying you’re about to spring on him. Lead counsel began by locking down the snitche’s story. “You’re sure it was February 17th?” “You’re sure he drove down from Philadelphia and got here on that day, February 17th?” “The night of the murders?”“Left to go back home the very next day, February 18th?” “You’re sure he was driving his blue Cadillac DeVille.” “That was the car he drove down from Philly?” “And that was the car he drove when you took him to the doctor’s house to do the robbery?” “It was just you and him?” “Nobody else saw either him or the car that night or the next day?” “So we just have your word for it?” The dimwit snitch had no idea what was coming. Once he was locked down, lead counsel began introducing the official documents I’d broght back from Delaware. He walked the jury through each step of my journey from getting the order signed here in South Carolina, to getting it countersigned in Delaware, getting the Clerk to issue the subpoena, and retrieving the certified copies of official documents from the repair shop. It was like the music from the movie Jaws was playing in the background, dun dun dun dun dun dun dun, the anticipation growing until the jury already knew there was a shark in the water circling the snitch before lead counsel introduced the documents proving our client’s blue Caddilac was in the shop the night of the murders.

The thought it might have been fairly easy for someone to have arranged to have the records available if needed them never crossed the jury’s mind. They acquitted our client of murder to the hushed astonishment of the courtroom. An acquital in a grisly murder case, involving a beloved doctor and his wife, by an out-of-state defendant, is an exceedingly rare occurrence. I vividly remember our client, bigger than I remembered him in CCI, stood up, shook lead counsel’s hand, and walked out of the York County courthouse door never to be seen or heard from again.

It was not my place to say whether our client may have been a made man in the Philadelphia mob capable of fabricating his Valentine Day defense. I was working as an associate of the law firm presenting our client, doing what I was instructed to do to. What most struck me was the realization how easy it could be for a person to be convicted of murder based solely on the word of a snitch. No fingerprints, no forensic evidence, no eye witnesses, no gold coins, nothing but the uncorroborated word of a snitch. But for his girlfriend smashing his windshield out on Valentine’s Day our client probably would have been convicted.